Rare Deep-Sea Dives To Almost 10 Kilometers Reveal Weird Deep-Sea Creatures Lurking In Japans Ocean Trenches

Here we bring together the latest deep-sea science, traditional knowledge, and expert insights that shape our work to safeguard these incredible habitats and species. Through blogs, interviews, fact files, and stories from those working in and with the deep, we shine a light on why the deep sea matters and why it needs our protection. Despite its importance, the deep sea faces significant threats, from deep-sea mining and overfishing to pollution and climate change. By protecting this fragile ecosystem, we’re preserving the life it holds, the climate it Deep Sea regulates, and the mysteries it continues to reveal.

News formats

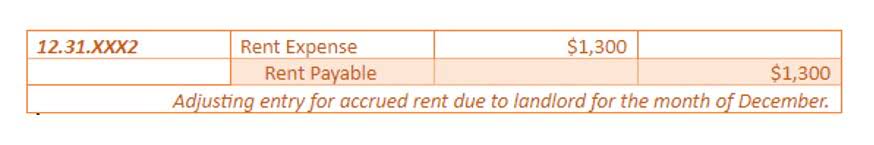

Yet significant uncertainties remain about the environmental impacts of this proposed industry, in which miners would send heavy machinery into the deep ocean to collect valuable minerals, such as manganese, cobalt, copper and nickel. Some animals can thrive by feeding on marine snow.2 In 1960, a bathyscaphe called Trieste went down to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, which is the deepest point on Earth. There aren’t any plants at all in these depths, so all fish in the deep are carnivores. This article will dive into the depths of the deep sea, exploring its characteristics, life forms, and why it is essential for the Earth’s health. In July 2025, a request was made for the ISA Secretariat to investigate whether deep-sea mining companies applying for licenses and permits under the United States’ mining code are at risk of violating existing ISA exploration contracts. UNCLOS prohibits unilateral mining activities, and mining companies may have exploration contracts revoked if found to be in violation of this.

More Critical Minerals Mining Could Strain Water Supplies in Stressed Regions

In popular imaginaries of the deep sea, expanding tendrils of fluid and smoke continue to evoke associations with war, fire, and contamination, ‘connected to hell itself’ (Ballard 2023). A realm governed by the vast timescales of geological and ecological processes—what Richard Irvine (2014) calls ‘deep time’—the deep sea has become a major geopolitical issue (Hannigan 2016), caught in a clash of competing temporalities. Despite the inherently slow epistemic process, scientists are working with urgency to fill critical knowledge gaps about its ecosystems before the accelerating mineral rush begins. In this high-stakes context, ‘getting (down) there’ is not only about reaching physical depths but also about navigating the tension between ocean preservation and industrial exploitation. Soon the skeleton is picked clean, but the fall is far from nutrient depleted.

What’s best for Earth? The debate over deep ocean mining

- These 31 contracts have been given to 22 contractors, with five of the contracts going to China through its government and companies.

- But the ocean floor consists of more than just the flat and seemingly vacant abyssal plain.

- There aren’t any plants at all in these depths, so all fish in the deep are carnivores.

- The very deepest depth of the ocean is roughly 2,000 meters deeper than Mount Everest is tall—36,070 feet deep (10,994 m)!

- Despite the challenges of exploring this extreme environment, advancements in technology have enabled us to uncover some of its secrets and begin to understand its importance to the Earth’s systems.

Tethered to a life at the surface because they require breathable oxygen, many large animals will make impressive dives to the deep sea in search of their favorite foods. Sperm whales, southern elephant seals, leatherback sea turtles, emperor penguins, and beaked whales are especially good divers. A Cuvier’s beaked whale is known to dive 9,816 feet (2,992 m) deep, and can stay down as long and 3 hours and 42 minutes, making it the deepest diving mammal in the world. As the sun sets, fish and zooplankton make massive migrations from the depths up to the ocean’s surface. Despite their small size (some no bigger than a mosquito), these creatures can travel hundreds of meters in just a few hours.

Introducing the Harvard International Roundtable

- By allowing the US to issue its own permits beyond its national border in EEZs, this executive order positions itself against the ISA.

- A glass sponge known as ”Advhena magnifica” in the Pacific Ocean being collected in 2016, at a depth of 2,000 meters.

- The deep sea is not just a scientific frontier; it is a reminder of the vastness and complexity of our planet.

- Later in 1524, the city was delivered to Governor Heitor da Silveira as an agreement for protection from the Ottomans.22In 1798, France ordered General Napoleon to invade Egypt and take control of the Red Sea.

- In 2018, scientists officially described a snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei) at 27,000 feet below sea level, the deepest living fish ever found.

- A Cuvier’s beaked whale is known to dive 9,816 feet (2,992 m) deep, and can stay down as long and 3 hours and 42 minutes, making it the deepest diving mammal in the world.

In these areas, seawater seeps into cracks in the seafloor, heating up as it meets molten rock beneath the crust and then rising again to gush out of seafloor openings. The water that emerges from them can reach temperatures of 400 °C and is extremely rich in minerals. Cold seeps are similar to hydrothermal vents as they also occur in tectonically active locations, but they emit hydrocarbon-rich fluids. The palette ranges from plastic bags and fragments, to glass bottles and the remains of fishing nets, to paint buckets. Packages and bags have been discovered that have apparently been on the seafloor for decades, virtually untouched by time.

Open Ocean Zones

The deep sea is not yet a distinct subfield within anthropology, nor is it likely to become one. It will probably be integrated into the broader domain of the anthropology of the ocean. Yet this does not diminish its significance as a site for anthropological reflection. On the contrary, the issues raised by scholars engaging with the deep sea are deeply anthropological in nature. They involve questions of otherness and estrangement, which unsettle terrestrial assumptions and challenge conventional ethnographic methods. The deep sea also invites to contemplate concepts such as chaos and disorder, and to critically examine the politics of corporate legitimacy.

It is a cold and dark place that lies between 3,000 and 6,000 meters below the sea surface. It is also home to squat lobsters, red prawns, and various species of sea cucumbers. Bits of decaying matter and excretions from thousands of meters above must trickle down to the seafloor, with only a small fraction escaping the hungry jaws of creatures above. Less than five percent of food produced at the surface will make its way to the abyssal plain. When the phytoplankton are gone, the animals that grew quickly to eat them die and sink to the seafloor. Finally, for the exploration of deep-sea mineral resources to continue, regulations should be transparent and collaborative, with participation from interested parties and key stakeholders — including ISA members, mining corporations and scientists.